Nutrient Testing

We now have vitamin and mineral test panels available that measure every conceivable nutrient.

First I’ll talk about the 5 most misleading nutrient tests, then I’ll explain why nutrient panels are inherently problematic.

If newer practitioners run these panels on their symptomatic patients, they see that they do have nutrient deficiencies – often several. Practitioners will also notice that there are many cases where giving nutrients based on these results seems to improve symptoms.

The patient tells the practitioner that they feel better, and the practitioner experiences a win. The beliefs are easily reinforced for all parties involved. Over time, contradictory evidence mounts. After working with people for longer periods of time, many who felt better at first start to relapse. After seeing the results of enough of these nutrient panels, it becomes clear that everyone tested had several deficiencies.

Yet the initial reinforcement of the beliefs makes them resistant to contradictory evidence.

I had some odd experiences early in my career that made me less apt to get stuck in these ideas.

My first exposure to one of the popular nutrient panels was through a patient of mine. He and his wife both came to see me as new patients. He was a salesperson for a vitamin-testing company. They wanted me to screen them for overall health including the tests from the company he worked for.

I was not yet familiar with the test but had no objections. It measured about 30 nutrients and claimed to determine their functional levels within the cells.

It is worth noting that he had few symptoms or complaints yet his wife had many.

When their results came back, he had only a couple of nutrients below ideal. His wife’s results were a mess. Nearly half of the nutrients were off, many by large degrees.

Yet their regular blood chemistry was quite different. Hers showed a healthy enough woman with early thyroid disease. His showed severe liver disease and were suggestive of late stage metastatic cancer.

Of course, blood tests alone can’t determine such things, but as he did further tests with the doctors I referred him to, my suspicions bore out. He died a few months later of stage 4 liver cancer.

My first experience with nutrient panels made me suspicious. Of course nutrient levels were never meant to be diagnostic of cancer. But it did not seem right to me that someone whose body had lost the ability to regulate itself should be in ‘better’ shape than a healthy person.

A few months later, other representatives of the same company approached me with hopes of getting me to use their vitamin tests. They offered to let me run a test on myself at no charge. I was skeptical for reasons in addition to the husband and wife’s results.

My first few months of practice were at a center that owned a medical clinic and a new testing laboratory. In addition to patient care, I was aware of the behind the scenes realities of blood analysis. I knew it was not a perfect science.

I accepted the offer to have my vitamin levels measured, but I wanted to use it as a test.

In our laboratory, the easiest way to see if the machines were working well was to analyze the same sample twice. Most blood tests require a small fraction of the blood that was collected in the test tube. That made it possible to re-run the test on the exact same sample.

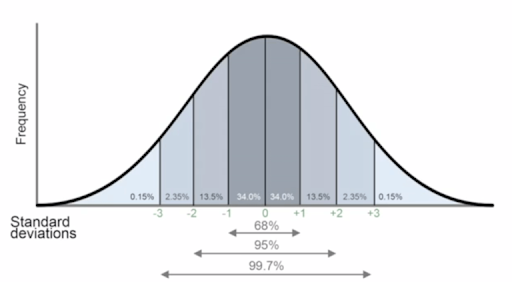

You might be surprised to know that the results are rarely if ever identical in these circumstances. Yet they should be close. Often they were not and it meant there was a problem with the process. This test was called a split sample and it is a common tool in reference labs.

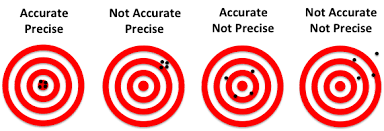

A split sample measures precision – does the test get the same results on the same sample? If the results are not precise, they are meaningless. If they are precise, there are more hurdles remaining. They must also be accurate and clinically relevant.

Clinically relevant means that the results direct the treatment into a helpful direction. Not all labs do this.

Imagine a bow-hunter. A precise hunter’s arrows always hit the same spot. It might not be the center of the target but they all end up close together. An accurate hunter’s arrows cluster around the center. A hunter who is precise and accurate gets all the shots close to the center.

Imagine a hungry hunter who goes out in the woods. A dozen well-paced shots into a tree won’t feed his family. They might be precise and accurate, but they are not relevant.

Precision is not everything, but it is easy to measure and without it, the test is useless.