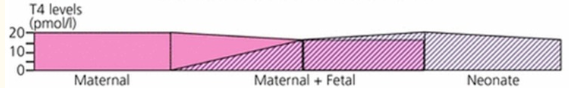

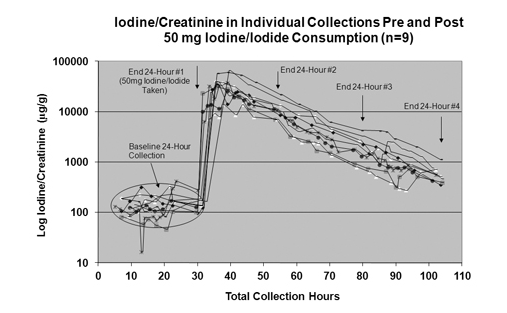

This chart illustrates why a mother’s levels can fluctuate quite easily. The needs are different because of a distinct transition that occurs.

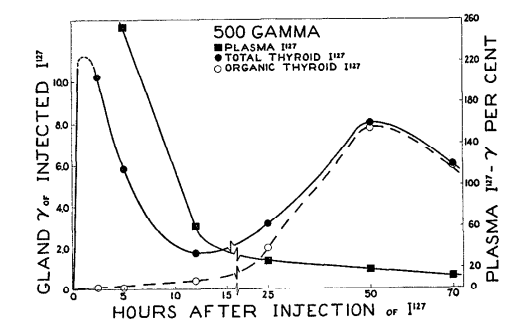

In the first trimester, the baby’s thyroid hormone comes from the mother, and as the fetus develops it slowly develops its own thyroid hormone, so it no longer needs it from the mother.

This is especially true for those in the late-second and third trimester because fetuses start making all of their own thyroid hormones by that point.5

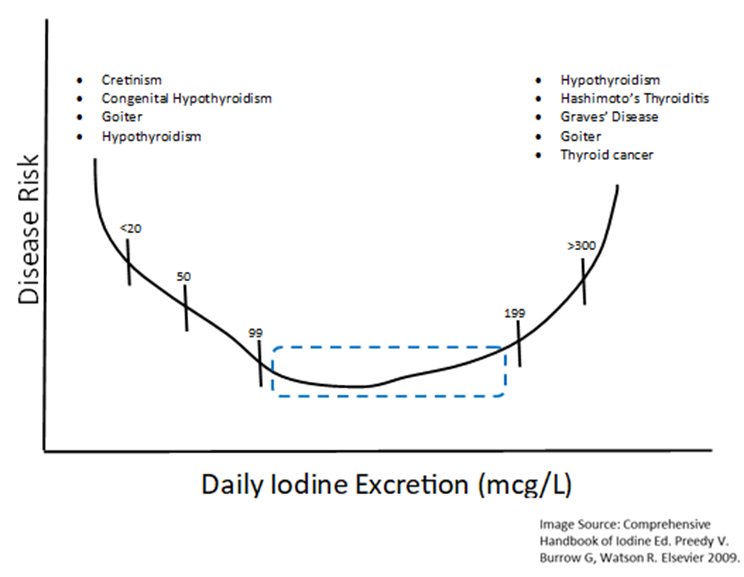

The largest study to date on iodine intake and thyroid function among pregnant women was just completed. It showed that women consuming just slightly excessive amounts of iodine had high rates of hypothyroidism, maternal hypothyroxinemia, and thyroid autoimmunity.6

Again, it is a matter of getting it right. Too little iodine during pregnancy could cause cognitive delays.

Thankfully that is no longer a common event. The most recent examples were Papua New Guinea in the 1960s and a remote province of China in 1990.

Both of these areas at the time had endemic cretinism7. This is a congenital disease from iodine disease, stemming from iodine deficiency.

It seems that with iodine in pregnancy mild deficiencies are less harmful on the baby and the mother than mild excesses. In the modern world, pregnant women with what was considered a mild to moderate iodine deficiency no longer have infants with developmental delays.8

How Much Iodine Is Best For Pregnant Women?

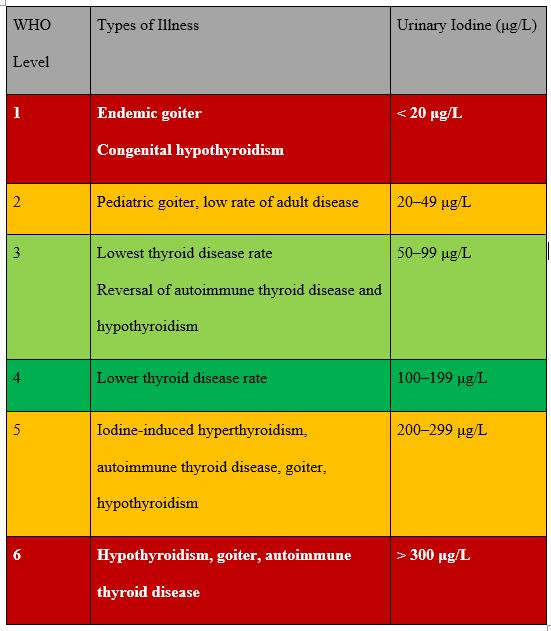

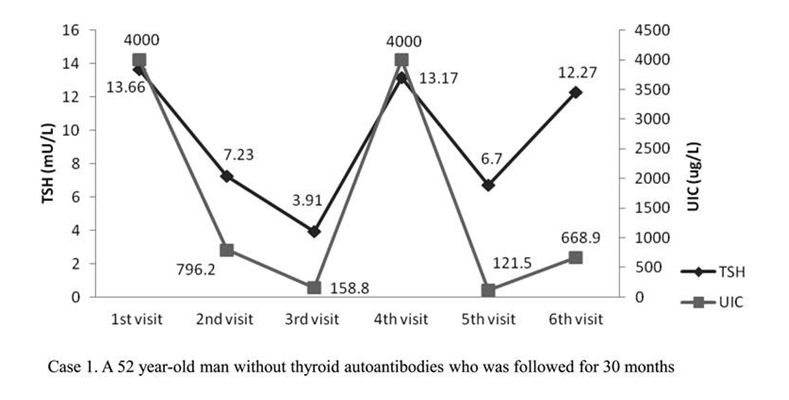

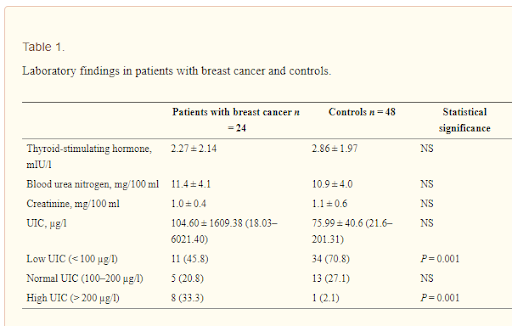

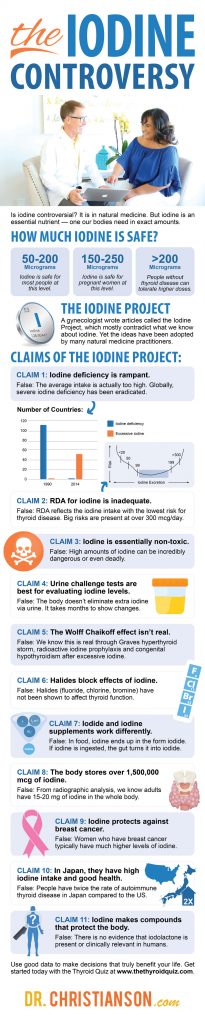

Complications emerge when mothers are under 50 mcg/L. Our latest guidelines suggest that the ideal range is a level of 150 – 250 mcg/L.

Let’s take the following passage for example:

“The risks of even mild iodine excess in pregnancy need to be carefully considered. The lowest prevalences of hypothyroidism, hypothyroxinemia, and thyroid autoimmunity, as well as the lowest serum thyroglobulin levels observed in the women with UIC of 150–249 µg/l”9,10

Do Pregnant Women Need Iodine Supplements?

The fact is that around 75% of obstetricians and midwives do not recommend iodine supplements for preconception, pregnancy, or lactation.11

In addition, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology does not recommend it. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists also does not recommend iodine supplements in pregnancy with the exception of geographic areas with overt iodine deficiencies.12

Finally, the American Thyroid Association states that:

“Without specific physiologic evidence of iodine deficiency in the United States at this time, and with the most recent U.S. survey reporting a median value of 173 g/L, which is within that currently recommended for pregnancy, the rationale for iodine supplementation during pregnancy is tenuous”13

A review, known as the Cochrane review, pulled together all of the current data over the last decade and culminated what we know about iodine during pregnancy.

They found that supplementing iodine during pregnancy:

- May worse nausea and vomiting

- May elevated maternal thyroid antibodies

- Has no clear effect on maternal thyroid disease

- Did not affect the rate of preterm births

- Did not affect the baby’s risk of thyroid disease14

- Studies on preterm infants have also shown no benefit to iodine supplementation15

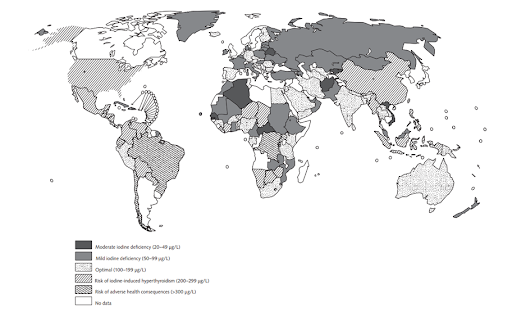

Iodine Deficiency Globally

If the US is not iodine deficient, what about the rest of the world?

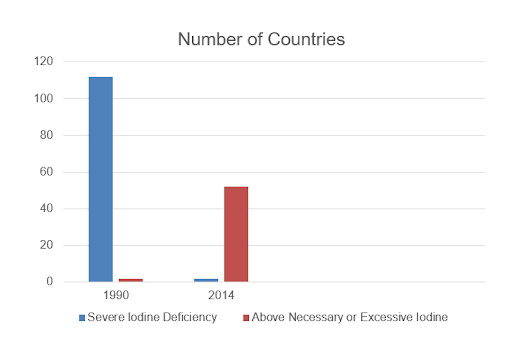

Globally, the idea of iodine deficiency has completely changed in the last few decades.16 Many nations used to be severely deficient, now none are.

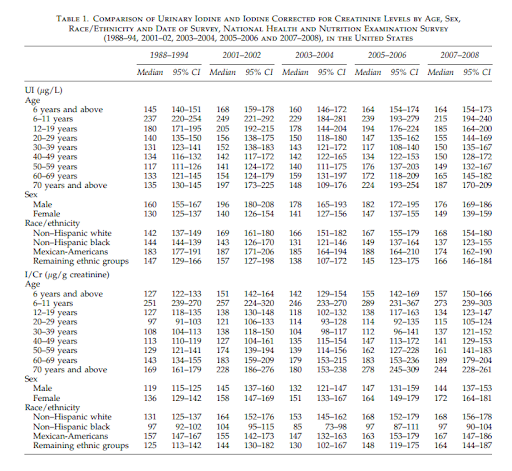

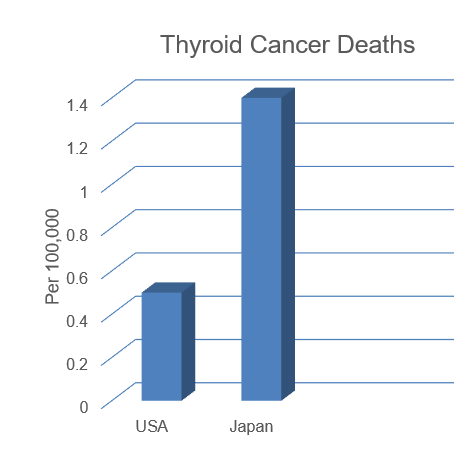

Let’s take a look at this quick comparison chart.